The Trouble with Street Turns

Welcome to the 104th edition of The LogTech Letter. TLL is a weekly look at the impact technology is having on the world of global and domestic logistics. Last week, I explained how overflowing email inboxes are like logistics technology integrations. This week, guest poster Brendan Tompkins, chief technology officer of Port Technology Services, explains why the industry has had such a hard time executing container street turns.

As a reminder, this is the place to turn on Fridays for quick reflection on a dynamic, software category, or specific company that’s on my mind. You’ll also find a collection of links to stories, videos and podcasts from me, my colleagues at the Journal of Commerce, and other analysis I find interesting.

For those that don’t know me, I’m Eric Johnson, senior technology editor at the Journal of Commerce and JOC.com. I can be reached at eric.johnson@spglobal.com or on Twitter at @LogTechEric.

Supply chain issues have been front and center of the American psyche and on the front pages of the newspapers since the pandemic. Fuel costs have skyrocketed, the industry is short on trucking manpower, and ports and roads are congested. From individuals to large manufacturers, the breakdown of the intermodal container industry has affected just about everyone. Perhaps most affected are our American exporters, who struggle to find shipping containers due to a shortage or dislocation of empty containers. The idea that we must do something about shipping and congestion is front and center.

The street turn revolution has been brewing in the industry for nearly two decades now - probably longer - and the practice is arguably the single most impactful thing we can do to solve some of the problems plaguing the industry. This one simple practice can reduce driver hours, save up to 50 percent in fuel for any given shipment, and reduce road and port congestion.

The terms “container triangulation,” “matchback,” and “street turn” are sometimes used interchangeably - but all refer to the process of reusing an import container, once emptied, to fill an export booking - outside of the marine terminals. If you are unfamiliar with what a street turn is in general, there’s a good discussion here that describes the process.

Street turns are done today, but on a relatively small scale, with very little impact on the issues mentioned above. Many motor carriers perform street turns when they can, but there’s never been a way to perform street turns at scale - at the required size to solve real supply chain problems. There have been fits and starts in the industry, with companies advertising their applications as the “Uber” of shipping containers, hopeful that their street turn model will finally disrupt the industry. Sadly, these models have largely failed, resulting only in small numbers of street turns. Even doubling or tripling the number of street turns being done today won't amount to a fraction of a fraction of the road miles and gate trips at our ports.

The distressing thing about our progress in this area is that the potential upside is astounding. Assuming a historical imbalance of 60 percent imports to 40 percent exports, and a volume of 50 million US TEUs per year, this means that we have the potential to save around 20 million empty truck trips…if we were able to source every empty export need from a street turn. At an average distribution center’s distance of 50 miles from the port, that’s 1 billion truck miles to potentially save. Twenty million gate visits at the port. Sixteen million trucker hours behind the wheel, and 153 million gallons of diesel fuel. That’s a fuel saving alone of nearly $1 billion annually. Say these numbers are way off, cut them in half, then again, and again, when will this revolution not be worth it?

And yet here we are, with barely any street turns being done. There are reasons this hasn’t been done. It’s hard. It’s complicated. There’s industry resistance. Vendors promising solutions have focused on only parts of the process. And while they can and do help companies perform street turns, these apps don’t help the scalability problem. To date, no scalable solution has been proposed or even attempted.

Someday, this revolution will happen and I believe this is an achievable goal: source all empty containers from the street, not the marine terminals. This will require a number of things, not the least of which are some willing stakeholders ready to try something new. But I think it can and will be done. Someday we will look back on what we are doing now and shake our heads at the enormous waste involved in sourcing empty containers from the marine terminals.

This is all knowledge gained from my own personal attempts at solving this problem, first in 2007 with a program at the Port of Virginia called “OTCS” (Off Terminal Container Solutions), and then in 2009 with an application/product I developed with a local motor carrier, StreetTurns.com. And finally, in 2014 with a full-blown, VC-funded startup, Quick180. All of these programs failed for one reason or another, but each taught me a bit more about the problem in general - what works and what doesn’t - and how to craft a model that I believe does work.

If street turns are probably the single most impactful thing we can do to improve issues across the shipping industry, why have we as an industry not done anything significant to address the issue and actually do street turns at scale? Why haven't we poured money into figuring it out, instead of squandering billions of dollars a year on wasteful empty truck trips, road and port congestion, demurrage, and other fees? Why have we accepted partial solutions that actually make things worse? It seems so simple…just let two motor carriers exchange a container. How hard can that be?

Well, like most things in the intermodal industry, things aren't so simple on the ground, and the fruit isn't as low hanging as it seems. I believe the reason we have not addressed the issue as an industry is that there are is are multiple problems to overcome to get this to work at scale. Any real solution must address all of these problems, account for them, and then perform the actual mechanics of executing a street turn.

In a future post, I'm going to be proposing a solution that does exactly this. But let me for now describe some of the difficulties faced in doing street turns at scale.

Matching equipment is hard: For a street turn, you must match an import container with an empty of the same size (40' or 20'), from the same shipping line and grade (paper, food, tobacco). So, for example, a container used for an Evergreen import of Chinese guardian stone lions will not be usable for a Cosco export of paper (requiring a very clean container) for multiple reasons. Some solutions focus on this with large marketplaces of container opportunities, but this can quickly become a needle in a haystack problem when approaching scale.

There's no visibility: To perform a street turn, you have to first locate an empty container somewhere away from the marine terminals. You have to know where the container is in order to decide whether or not the triangulation makes sense. This, believe it or not, is rather difficult in our industry. It turns out that almost no one knows the location of empty containers except for the motor carrier and the customer. In many cases, the port doesn't even know where the containers are destined. This is because no one wants to let the world know who or where their customers (and containers) are. Because of this, most street-turn systems rely on companies volunteering this information. Most won't do this, and efforts that rely on this model have languished with relatively small numbers of street turns. I've tried this approach before with StreetTurns.com and this was the issue I faced.

Timing is an issue: You need to know "when" a container will become empty and available. Just because there's an import container sitting in a motor carrier's lot or at a BCO, doesn't mean it's empty and ready for re-use.

They are laborious: It takes someone (a dispatcher or import manager for example) time to set up a street turn, find and coordinate the drop-off location, and deal with any issues that arise. As a result, many motor carriers largely only perform street turns with their own drivers, where there's already a communication channel open and issues are easily fixable.

There's competition: An import motor carrier likely views their empty container as something that has value (it does, and more on that later) and doesn't want to give something of value to a competitor, or at the very least views their participation as something that should be compensated for.

Diminishing rates: Motor carriers are worried their dray rates will plummet as their customers demand to pay only for one-way moves, instead of the roundtrip to and from the ports.

Dray rates are already low: Depending on the distance of the move from the port, dray rates may be so low, that the overhead only leaves tens of dollars of profit, and not much room for cost savings. When it takes time to arrange and execute a street turn, many may simply return to the port to pick up an empty.

There's a perception that you need permission: Believe it or not, street turns were once specifically prohibited by the UIIA agreement which governs equipment use. This changed in 2015, but most would assume you need to ask the steamship lines if you can do a street turn. This is not the case, you only really need the authority.

You need Authority: You do need authority to do a turn. Truckers cannot do this themselves, they do need a UIIA signatory party to issue an interchange.

There's a chassis, too: It's not just the container. Without lift capability outside the port, the chassis under that container is also under the care and custody of the import motor carrier. If the chassis was rented from a chassis pool, the chassis pool needs notification too. If not, and it's an owner's chassis, there needs to be lift capability outside the port, and that is not a common capability.

There's industry resistance: There's a perception, especially with parties who hire union labor, that street turns will spark labor issues, and that labor unions will see street turns as something that threatens union work. Specifically, a worry that the maintenance and repair of chassis will go down and a reduction in gate traffic will require less gate labor. Because of this, ports have been reluctant to embrace the practice, even though they know it's good for business. Any scalable solution will have to address concerns that ports and labor unions have.

Again, any solution with hopes of working at scale must address all of these issues, and the solutions that have been tried, and are currently being tried tend to focus on solving one of these issues to the exclusion of the others.

Editor’s note: I’ll either append Brendan’s piece on solutions to the street turn dilemma to this newsletter or (more likely) send out a supplemental newsletter focusing on those solutions. Stay tuned!

TPMTech Agenda is Live!

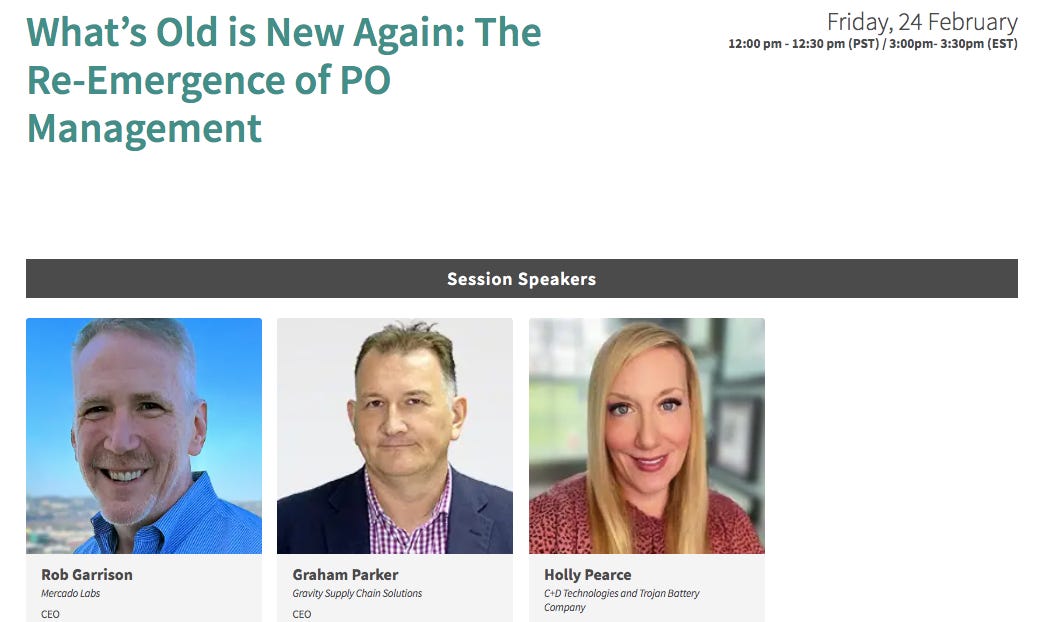

Because we put editorial-focused discussion first at the Journal of Commerce, we generally know pretty far in advance exactly what we want to discuss at our events. TPMTech is no different. The agenda for an event more than four months away went live this week. There’s lots more speakers to announce, a few more sessions to come, and a new wrinkle we’re adding this year that’ll be unlike anything you’ve seen at a logistics technology conference. Use the promo code below to get a 25 percent discount on TPMTech registration, or a bundle with TPM.

Can’t wait to share more with you, and more importantly, to see you in Long Beach in February. Here’s one session that’s already set:

Neal Peart Lyrics of the Week:

A thousand years have come and gone

But time has passed me by

Stars stopped in the sky

Frozen in an everlasting view

Waiting for the world to end

Weary of the night

Praying for the light

Prison of the lost, Xanadu

Here’s a roundup of recent pieces on JOC.com from my colleagues and myself (note: there is a paywall):

Wrote yesterday about Transfix putting its plans to go public via a SPAC on ice due to the faltering stock and freight markets. We’ll now have to wait until Freightos goes public (likely in Q1 ‘23) to get a test of the public market’s taste for newer logistics technology entrants.

Wrote about the highlights of a truckload procurement technology session at the JOC Inland Distribution conference in late September here. The focus was on avoiding seeing tech as a means to predict price and instead using it to build adaptability.

Interesting partnership on trade finance between project44 and the Global Business Shipping Network (GSBN). The GSBN has been busy of late, announcing eBL product developments and a pilot with Hapag-Lloyd and the Bank of China to convey shipment data from a shipper to the bank. CEO Bertran Chen told me these are all related, using GSBN as the common infrastructure.

Portchain has added the DP World-run Antwerp Gateway terminal to its growing roster of clients for berth planning optimization tools.

And here are some recent discussions, reports, and analysis I found interesting:

My friends at AlixPartners with a great rundown of the fast changing ocean freight environment from the buyer perspective.

Trade expert Caroline Freund at PIIE with a very informative look at how goods demand - not necessarily supply constraints - has driven price inflation.

Speaking of Caroline, this tweet should put to rest the idea there’s already been a massive shift away from global sourcing…

But meanwhile, Anthony Miller bringing the heat on what’s to come in global supply chains…

A very worthwhile blog on microservices in supply chain from Blue Yonder.

Pete Mento joined the NYSHEX podcast this week, and that’s an automatic share.

Interesting webcast later this month on incorporating visibility for forwarders with Brian Glick of Chain.io.

Here’s the replay of my conversation with Rob Garrison, CEO of Mercado Labs, on his Let’s Talk Supply Chain show First Things First. This was super fun and Rob turned the tables on me, asking me who my favorite band is.

And if you missed my conversation last week with Samantha Jones of Rocket Shipping on LogTech Live, here’s the restream.

Some upcoming events I’ll be involved in:

My guest at 10 am ET Oct 21 on LogTech Live will be Rob Petti, CEO of Prompt, and author of this guest post on The LogTech Letter. As always, subscribe here to see past episodes and get alerts on future guests.

I’m leading an hourlong JOC webcast Oct. 27 on how technology can be a differentiator for 3PLs with my friends Angela Czajkowski, Mike Powell, and Robert Khachatryan. Register here for the free event. This will be a great discussion!

Joining an all-star crew from Searoutes, Intelligent Audit and Vizion at 11 am Nov. 1 to discuss why context is important when using visibility data

Disclaimer: This newsletter is in no way affiliated with The Journal of Commerce or S&P Global, and any opinions are mine only.

This is my favourite of your articles in a while. The street turn business is so, so interesting. Its the epidomy of logistics tech as it:

1. Is an undigitized process that looks likely to be eaten by tech

2. Is a huge addressable market

3. Is justifiably one of the "eliminating wasted empty miles" targets for innovators

4. But absolutely has failed to be solved, 100% for controllable (though hard) reasons.

Like Paul Graham said: on one hand, entrenched protocols are impossible to replace. On the other, it seems unlikely that people in 100 years will still be living in the same container drayage mess we do now. And if it is going to get replaced eventually, why not now?

Great article as always! Curious to hear more about your learnings from StreetTurns.com, in particular on the incentives for companies to volunteer location of empty containers.

Are there any industry players who attempted this recently with some degree of success?