What Magic and Bird Can Teach Us About Xenophobia

Welcome to the 81st edition of The LogTech Letter. TLL is a weekly look at the impact technology is having on the world of global and domestic logistics. Last week, I revisited the issue of electronic bill of lading adoption. This week, I’m posing a hypothetical: will bootstrapped business in the logistics technology space end up faring better than those that are venture-backed?

As a reminder, this is the place to turn on Fridays for quick reflection on a dynamic, software category, or specific company that’s on my mind. You’ll also find a collection of links to stories, videos and podcasts from me, my colleagues at the Journal of Commerce, and other analysis I find interesting.

For those that don’t know me, I’m Eric Johnson, senior technology editor at the Journal of Commerce and JOC.com. I can be reached at eric.johnson@spglobal.com or on Twitter at @LogTechEric.

When I was a kid growing up in Los Angeles in the 1980s, here was the list of things I cared about:

My mom and dad

The Los Angeles Lakers

Nuclear war with the USSR

That was it. In the mid-1980s, there were simultaneous cold wars going on: the US vs the USSR, and the Lakers and the Boston Celtics. In both wars, you had to choose sides, and you could not be a neutral. One side represented good, and the other evil. It was existential stuff. To say I lived vicariously through the Lakers would be somewhat of an understatement.

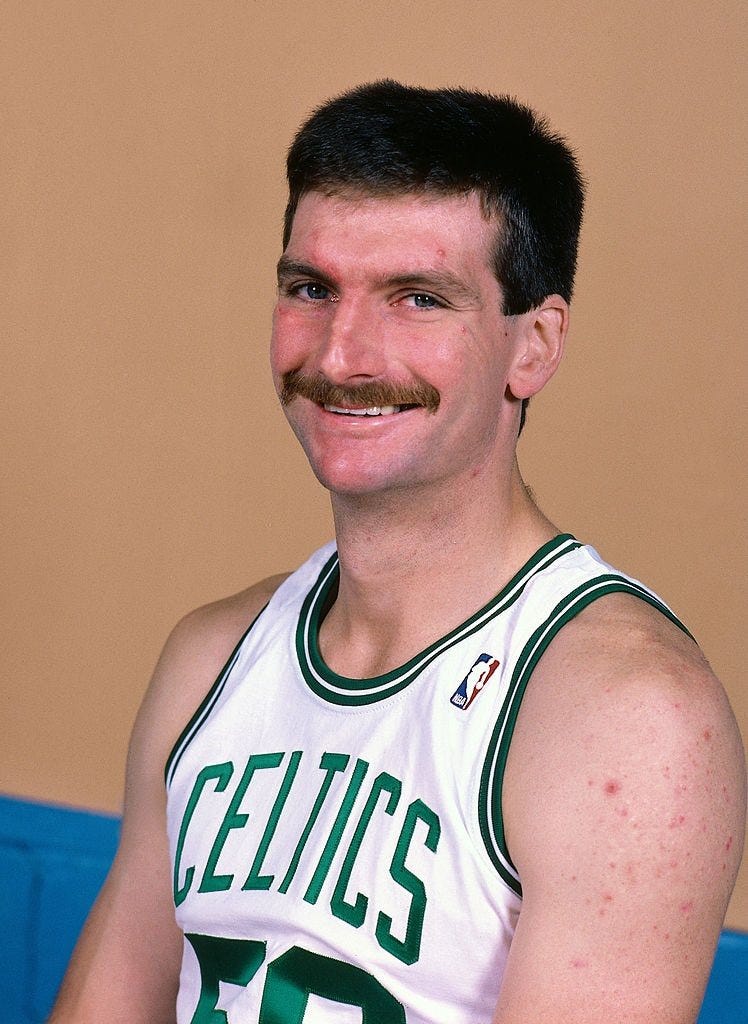

When they vanquished the dreaded Celtics, it felt like the whole world was in its proper order. When the Celtics won, it felt like the beginning of the end of the world. Wait, the bad guys aren’t supposed to win in the end. The Lakers had Magic Johnson, the most entertaining, captivating player to ever grace the league. It was electric, fast-breaking, showbiz basketball. The Celts were plodding rednecks with skeezy mustaches who played dirty and took full advantage of their decrepit barn of an arena.

At the heart of this blood feud were Magic and Larry Bird, two generational players who were essentially each other’s yin and yang. They hated each other, then respected each other, and eventually came to love and appreciate one another. The reason is that each one pushed the other to heights that would have been impossible had the other not existed. A league without Magic and the Lakers would have allowed Bird and the Celtics to rip off six or seven titles. A league without Bird and the Celtics might have meant the Lakers could have plundered an additional title or two.

But the rivalry was symbiotic - both teams benefited from the other’s presence. The ‘80s were more memorable because two of the greatest teams ever assembled had a worthy foil. They had highs and lows that mattered. They tooketh and gaveth back, and that give-and-take didn’t just make things more interesting, it made things more valuable.

So where am I going with this? Let me fast forward to today, to a topic that has nothing to do with basketball. Global trade, and the logistics pipelines that support it. Over the last couple weeks, I have seen several tweets, read a few missives, and watched a few interviews, where figures positioning themselves as experts on global supply chains have floated the idea that China’s zero-COVID policy in Shanghai is part of some nefarious plot to make Western economies suffer. The theory, which ventures straight into conspiracy, is that the powers-that-be in China believe their people and economy strong enough to withstand a withering total lockdown of the country’s leading financial hub as a sacrifice to take down countries that are overly reliant on China’s export prowess.

Let me be clear: I am not, in any way, a China insider. I have absolutely zero certainty about the motivations for China’s policy in Shanghai and other regions affected by the zero-COVID policy. From what I’ve read, the leading factors are a desire to contain the virus in a way that more democratic countries aren’t able to - this would be the version that China would probably like the world to believe. Another reason may be political, ie an internal struggle between party factions in Beijing and Shanghai. And then there’s the “grand plot” theory: that by constricting global supply chains at their source, China can somehow exact its power over western nations.

It’s certainly easy to fall into the trap of believing in nefarious motivations. Information out of China is controlled by the state. Things seem opaque by design. But believing in this version of the Shanghai lockdown story is believing in the power of xenophobia. It’s fearing that which is different as opposed to embracing it, recognizing that just because people have different motivations doesn’t make them evil. It’s a 10-year-old kid believing that Larry Bird was, in fact, the worst person in the history of the world, as opposed to being the exact thing that the best person in the history of the world, Magic Johnson, needed to become truly legendary.

Let’s clarify some things here: there are issues with the way China engages in the global trading system. The technology transfer mandate for foreign companies doing business in the country is clearly a problem. The extent to which private sector companies outside China must compete with state-owned entities is a problem. Market access to China for US exporters is a problem. The horrific situation in Xinjiang is obviously a massive problem. But viewing things through the lens of a cold war with our biggest trading partner is hardly the solution.

The major difference between the actual cold war between the US and USSR is that those countries were not economically coupled in such a way as to be reliant on one another. It was the opposite, in fact. Both countries spent absurd amounts in a race to create the perception that they were an indomitable force. The US and USSR were trying to build the tallest ivory towers. The difference now is that the US has spent the last 20 years transitioning its economy to run on inputs and finished products from China. China has spent the last 20 years relying on US consumers and manufacturers to grow its prosperity. China and the US are more like an intertwined DNA strand. It’s a cold relationship, not a cold war.

I’m not blind to the moves China has made to create less of a reliance on western consumers. It has a hunger for resources and for naval control that is at odds with US interests. Not to “both sides” the situation, but the US also has made strides to lessen its reliance on China and to diminish China’s power. But it has also left opportunities by the wayside. The abandoned Trans-Pacific Partnership looms very large in this respect. As time marches us further away from that fateful decision, as the calls to nationalize, to return supply chains to Western shores, to move to Mexico instead of China, intensify, it becomes clearer to me day-by-day. The US vs China is not a redux of the US vs. the USSR. It’s a redux of the Lakers vs. the Celtics. Two powerful sides that don’t see eye-to-eye, who are constructively wary of one another, who are competing for finite resources, but who eminently need one another.

Imagine a world where the two largest economies in the world are completely decoupled. Some imagine that and feel a sense of euphoria. Some see the lockdowns as impacting the future of manufacturing decisions in the near term. I see it and think, why would I purposely close off half of my house, even if some of those rooms need some repairs? We can indulge in our darkest impulses, that others are evil and wish us harm - that they would even harm themselves to harm us more. Or we can stop countenancing xenophobia from the people who proclaim themselves supply chain experts and figure out how to engage with difficult, but necessary partners.

Here’s a roundup of recent pieces on JOC.com from my colleagues and myself (note: there is a paywall):

Freightos had me at “ocean carrier APIs” with their latest research foray. I wrote about how Freightos found that container lines are eager to funnel more electronic quote and booking requests through their own websites over third party sites to drive more use of ancillary logistics services.

I spoke three times with Tive founder Krenar Konomi over late 2021 and early 2022 to better understand where his sensor-based visibility company was and is going. That all came ahead of a $54 million fund round the company snagged last week.

A month ago, I wrote this newsletter about the confusing nature of all the public sector supply chain data initiatives out there right now. And I circled back to it in this piece for JOC.com.

Kind of crazy that a $260 million funding round (along with a $150 million line of credit) is only the fourth bullet point in this section. But here we are. Convoy’s latest round values the company at $3.8 billion. Everybody’s got their opinions on this company, much like with Flexport (with whom Convoy partners, incidentally). What stands out to me is that Convoy has tried to carve out distinct products that, even if they aren’t new to truckload brokerage, are novel when viewed through the lens of their app-first model. Remember, my first priority is determining whether a system or provider is doing something interesting for the market, not necessarily what their margin is.

Finally got a chance to recap our JOC webcast a couple months back on the future of digital freight procurement. Highly encourage you to catch the on-demand version: so many worthwhile tidbits to consider. But I recapped here the extent to which automation may start to figure more prominently in ocean and truckload procurement, even in long-term contract scenarios.

And here are some recent discussions, reports, and analysis I found interesting:

Convoy CEO Dan Lewis went into the benefits of the company’s Guaranteed Priority product here.

If you’ve seen the terrifying map of all the “ships” waiting to berth in Shanghai, realize that image is not very useful for actual cargo owners.

My colleague Rahul Kapoor does a fantastic job of dispelling all the nonsense here.

Clickbait around the extremes of the freight market are easy to find. If your business model is set up to succeed when things are volatile, you have an incentive to try to drive the perception of perpetual volatility. Yes, sober analysis is more boring, but it’s always more valuable. Jason Miller is pretty much a go-to for me in that regard. He’s prolific on LinkedIn. There’s always, of course, Bill Cassidy, when it comes straight reporting on the domestic market.

Are you subscribed to Cathy Morrow Roberson’s Freight Forward newsletter yet?

Some upcoming events I’ll be involved in:

I’ll be in the Big Easy next week with some of my JOC colleagues, leading a visibility panel at our JOC Breakbulk and Project Cargo Conference April 25-27 in New Orleans. My session, with representatives from Voyager Portal and FuelTrust, is at 4:25 CST April 26. Still time to register here.

I’m leading a range of sessions on digitization in global ports at the IAPH World Ports Conference May 16-19 in Vancouver. This is going to be a fantastic gathering of the world’s leading ports, terminals and maritime decision makers. Here’s the agenda, and click here to register.

I’ll be moderating a panel on how the freight industry can gird itself against the threat of cyber attacks at the NITL Virtal Transportation Summit May 24-26. See the full agenda here.

Disclaimer: This newsletter is in no way affiliated with The Journal of Commerce or S&P Global, and any opinions are mine only.